In January 2026, Amsterdam’s municipal council voted to prohibit meat advertising in publicly owned public spaces, marking one of the first instances of a national capital directly aligning municipal advertising policy with climate and public health objectives. The measure passed with majority support and is scheduled to take full effect on May 1, 2026, with implementation phased in as existing advertising contracts expire.

The policy applies to city-controlled billboards, transit shelters, and other publicly managed advertising infrastructure. It does not ban meat consumption. It does not prevent restaurants from serving animal products. It does not restrict private businesses from advertising on private property.

Instead, it draws a narrower line:

What should taxpayer-funded public space promote?

Supporters of the measure argue that livestock production contributes significantly to greenhouse gas emissions, land-use change, and biodiversity loss — issues that Amsterdam, like many cities, has committed to addressing through climate initiatives and sustainability planning. From that perspective, allowing public infrastructure to promote high-emission products appears inconsistent with stated environmental goals.

Critics, however, frame the decision as government overreach, raising concerns about fairness, industry targeting, and market freedom. Agricultural and food-sector representatives have questioned whether restricting advertising in public space unfairly singles out certain products.

These debates are not new.

Cities have historically regulated advertising categories when public health or safety concerns reached consensus. Tobacco ads once saturated transit systems and billboards before restrictions became common. Fossil fuel advertising has come under increasing scrutiny in climate-conscious municipalities. In each case, the question was less about prohibiting individual consumption and more about whether publicly managed space should amplify specific commercial messaging.

Amsterdam’s decision signals a shift in how advertising itself is understood.

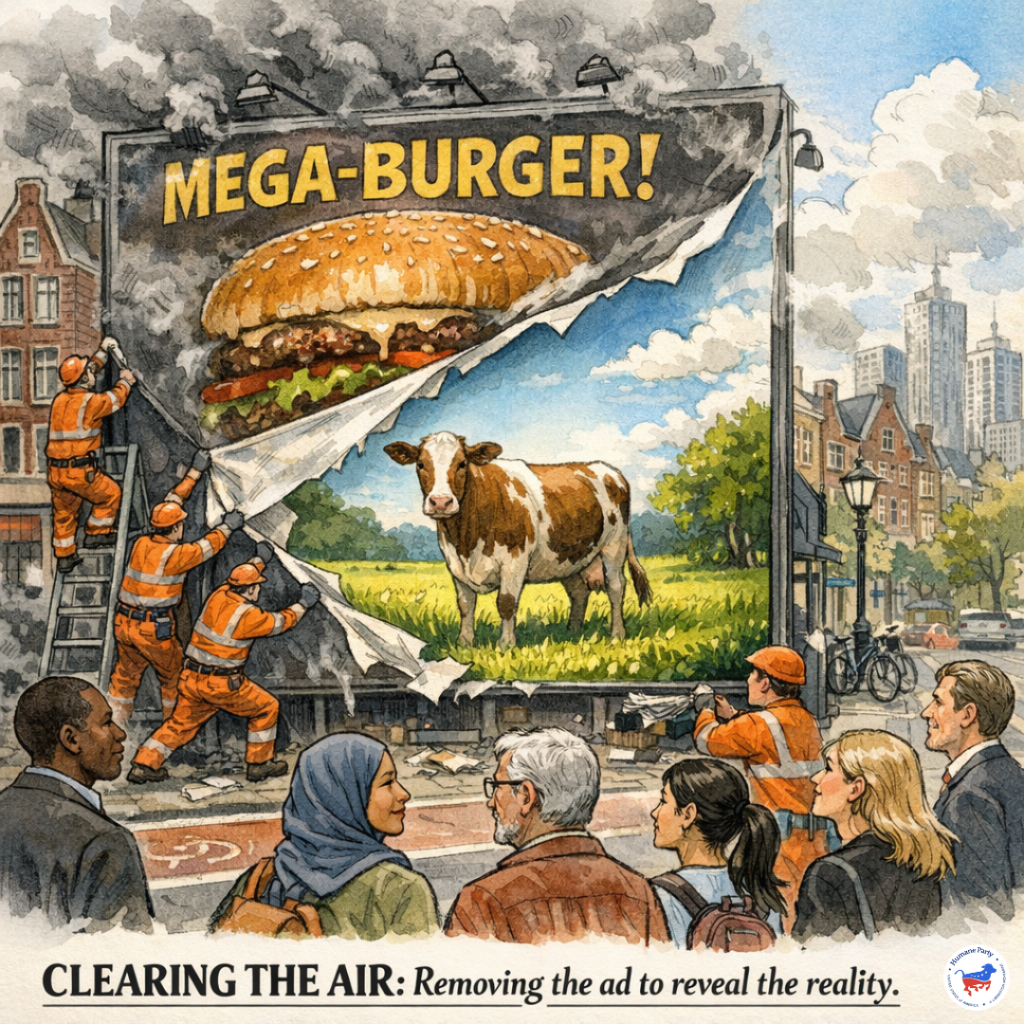

Advertising is often treated as passive — as though it merely reflects consumer demand. But it does more than mirror culture; it shapes it. It signals what is normal, desirable, affordable, and aspirational. Billboards rarely depict supply chains, methane emissions, deforestation, or the environmental footprint associated with the products they promote. Marketing simplifies. It beautifies. It edits.

This policy, in effect, edits the editor.

By declining to promote meat products in city-controlled spaces, Amsterdam is asserting that public messaging carries civic weight. Public infrastructure, the council suggests, is not value-neutral real estate but an extension of policy and identity.

The broader question extends beyond one product category or one city.

As municipalities invest in climate adaptation, public health systems, and sustainability frameworks, they may increasingly examine whether their advertising revenue streams align with their stated priorities. The issue is not whether individuals may choose what to consume. It is whether public institutions should actively promote industries that complicate publicly declared environmental goals.

Public space has always reflected public values — in monuments, in transit systems, in zoning decisions, and in the messages displayed across city streets.

Amsterdam’s vote does not end debate. But it does formalize a growing conversation:

If cities are serious about climate commitments, should their billboards be as well?